Misogynistic Gym Bros and Katy Perry Remixes: What is “Gym Hardstyle Music” Doing to Young Men

Misogynistic Gym Bros and Katy Perry Remixes: What is “Gym Hardstyle Music” Doing to Young Men

David Laufer

Further reading:

Ebare, S. (2004). Digital music and subculture: Sharing files, sharing styles. First Monday, volume 9, number 2 (February 2004). http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue9_2/ebare/index.html

Goriunova, O. (2016). The Force of Digital Aesthetics. On Memes, Hacking, and Individuation. The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, 24(47). https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v24i47.23055

Kim, S. A. (2018). Social Media Algorithms: Why You See What You See. 2 Geo. L. Tech. Rev. 147. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/gtltr2&div=12&id=&page=

Williams, J. P. (2006). Authentic Identities: Straightedge Subculture, Music, and the Internet. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(2), 173–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605285100

GLAAD. (2021). GLAAD Accountability Project. Ben Shapiro. [cit. 04.12.2022]. https://www.glaad.org/gap/ben-shapiro

Holpuch, A. (2022, 24). "Why Social Media Sites Are Removing Andrew Tate's Accounts". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/24/technology/andrew-tate-banned-tiktok-instagram.html

Javed, Saman (2022, 22). "Andrew Tate: Who is the controversial TikTok influencer?". The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/andrew-tate-unbanned-twitter-who-is-b2229545.html

Johnson, N. (2020, 13). How Hyperpop Gives Trans Artists a Voice. RingTone Mag. https://www.ringtonemag.com/articles/how-hyperpop-gives-trans-artists-a-voice

Walker, S. (2021, 4). 404 Error, Genre Not Found: The Life Cycle of Internet Scenes. Complex. https://www.complex.com/pigeons-and-planes/life-cycle-of-internet-genres-scenes-hyperpop-digicore-cloud-rap

Looking for a recipe for quick online success? Take Katy Perry’s 2008 hit “I Kissed a Girl,” speed it up, overlay it with a loud pumping hardstyle beat, throw in an image of sweaty muscular men, and upload it to YouTube. If you’re anything like users Tevvez2.0, Whippa, Gikoloz, and others creating ‘hardstyle’ remixes of pop songs, you’ll get millions of views, hundreds of thousands of likes and hundreds of people with anime profile pictures commenting “♥♥♥” to express their joy at finally finding a suitable track for their gym sessions (usually with a variation of the slogan: “WE GO GYM!”).

‘Gym internet music’ is making waves, apparently, and shows how various online subcultures can reveal a treasure trove of things that’ll rip your ears off and leave you longing for more. Clicking through these sonic rabbit holes, however, can also quickly lead to dark places you may wish you hadn’t discovered.

Meme music seems to be the next big thing. Robloxcore, Dariacore, Signalwave, Sigilkore… British and American media have described such eclectic experimental scenes deep fried in internet culture as the future of pop for gen Z. But despite their attractively unhinged Bit- and soul-crushing nature, a quick scroll through SoundCloud still reveals this type of music to be a very niche thing. Look beyond a few select trends, and you’ll quickly find songs with a similar aesthetic buried in the internet depths, doomed to oblivion. The chronically online revolution isn’t happening for everyone. Hectic furcore “tinnitus speedrun” attempts, borderline illegal lolicore mixes, breakcore versions of traditional Czech folk music. It’s all here for the passionate insiders to enjoy, but in the outside world, no one is really paying attention. You probably won’t catch your classmates gushing over “funnycore twerkhouse” anytime soon.

It is all the more surprising, then, to discover one particular trend booming in such a big way. The combination of hardstyle—a hard hitting electronic dance genre originating from turn-of-the-century Netherlands rave scenes—and gym culture—which adapted the music’s frantic beats and high-octane energy to serve as the perfect workout music—created the fertile soil for the birth of a new social media trend.

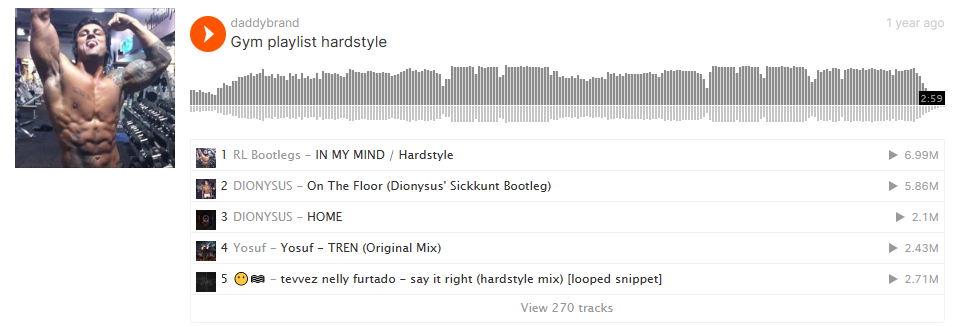

By uploading hardstyle- and gym-themed remixes, often of 00’s and 10’s radio hits, users get substantial algorithmic traction across platforms. Their YouTube and SoundCloud profiles work as ideal ‘viral factories’, posting content reminiscent of the nightcore trend of the early 2000s—simple, formulaic remixes with generic beats inserted into sped-up popular songs. Due to their simplicity, these tracks can be dished out one after the other, pleasing the platforms' algorithms. The more user activity, the more social networks earn.

Tracks related to gym and hardstyle amass millions of plays across platforms

Pumping out the Hardstyle BangersBut why are these tracks so popular? As with much of today's teenage internet culture, TikTok plays a big role here. Videos with the hashtags #gymmusic or #gymhardstyle garner tens of millions of views, featuring jacked up guys recommending the best bass-boosted mixes with chipmunk vocals, or showing heavily edited fancams of bodybuilders intended to juice up your next bench press session. These songs and videos function as memes—they contain strong visual and edited language, humor, remix, are easily and virally replicable, encourage further dissemination and, most importantly, help unite a specific community around a shared topic.

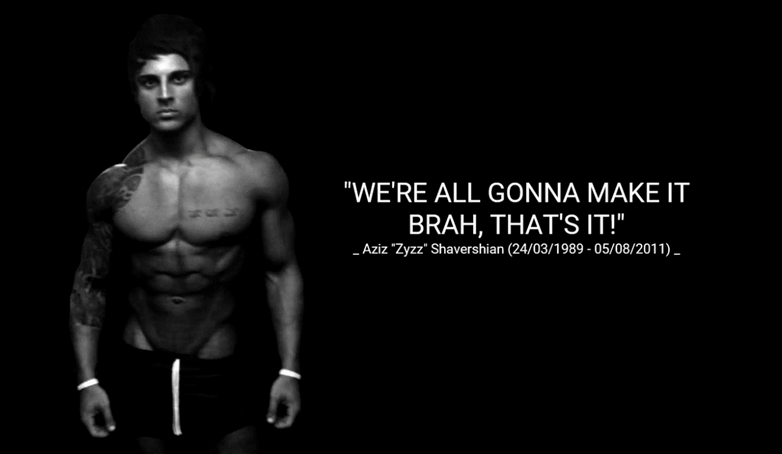

Another related hashtag almost always appears with the songs: #zyzz. The connection between hardstyle and working out is partly owed to Aziz Shavershian (known as Zyzz)—an idol of the online bodybuilding community, fitness influencer, and a die-hard fan and promoter of hardstyle. Famous for his perfect figure, internet trolling, and steroid use, this Australian bodybuilder gained cult status in the last decade following his untimely death in 2011 at the age of just 22.

Zyzz's love of working out and hardstyle is the inspiration behind a specific genre of very popular gym remixes called ‘Zyzz hardstyle’ or ‘ZYZZCORE’. Compilations titled “When the Zyzz Music Kicks In” are used by millions of users as the ultimate workout motivation. These compilations feature banging tracks by the artist Tevvez, a staple in the Zyzz-lovers community, accompanying videos of men pushing the physical limits on how big a person’s biceps can possibly get. Shavershian was even recently celebrated by Australian producer Flume, who performed alongside Zyzz's brother and a group of oiled-up bodybuilders, showing how this trend is reaching mainstream music as well.

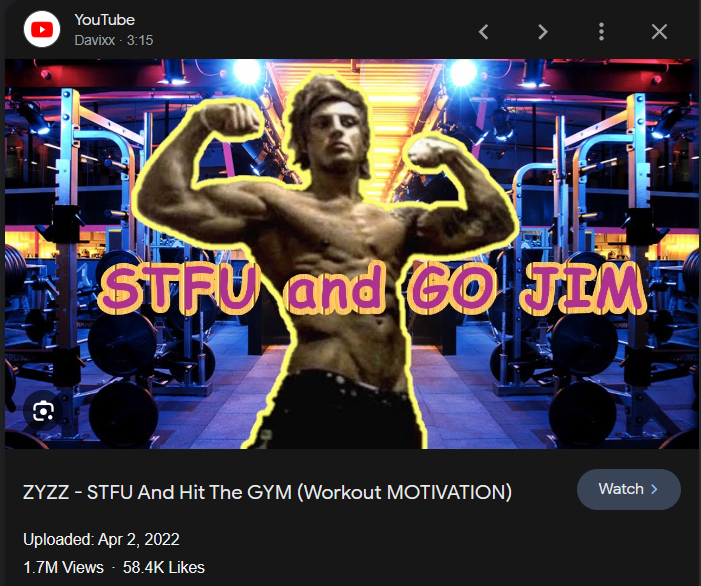

The popularity of motivational workout content on YouTube is skyrocketing.

Disregard Females. Acquire AestheticsOf course, this could just be harmless fun. The character of Zyzz, however, who is almost always mentioned in the captions, titles, and hashtags of these ‘fun’ remixes—be it of Katy Perry, Maroon 5, or Lana Del Rey—raises many red flags. Zyzz became famous for numerous posts circulating on the Bodybuilding Forum and 4chan’s fitness section, in which he preached recipes for the ‘perfect’ lifestyle: exercise 5 times a day, drink vodka, be an alpha male, “disregard females, acquire aesthetics.”

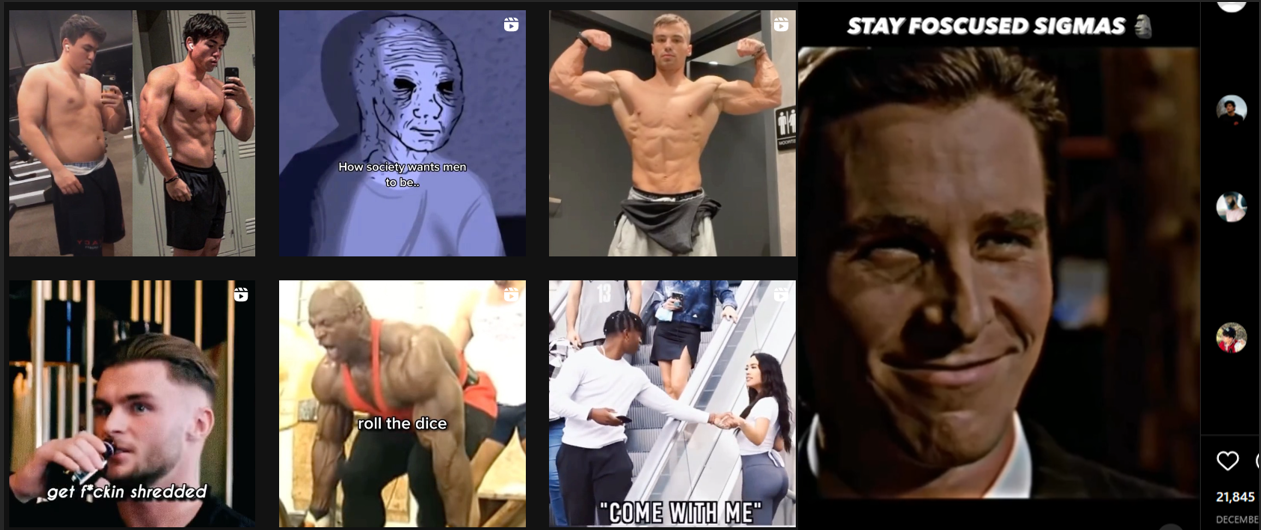

To this day, Zyzz is an icon of fitness TikTok ( ‘GymTok’) and a number of TikTok and Instagram profiles which post memes, inspirational photos, and videos adoringly showing off his muscles and masculinity, while at the same time body-shaming those whose bodies look different. “One of GymTok’s biggest problems is its obsession with ‘masculinity’ and eliminating ‘weakness’” writes Lucca Swain for The Owl.

The Instagram profile @zyzz_page is overflowing with photos of absurdly muscular men, whilst its frequent collaborator profile @gym_or_meme, makes fun of guys who are overweight or wear makeup. Zyzz and others like him thus serve as an inspiration and pipeline for body-shaming content, sometimes causing muscle dysmorphia (also called ‘bigorexia’)—a kind of reverse anorexia, a chronic idea of ‘being too small’ and an obsession with gaining muscle and working out. “The never-ending scroll of six packs and boy-band faces makes [young men] feel inadequate and anxious,” writes Alex Hawgood for the New York Times, describing the influence of social media on the development of the illness.

The IG profile @zyzz_page compares the sons of Arnold Schwarzenegger. [Collage].

The problems of beauty standards promoted by online environments were, until recently, addressed in the media and academia mainly for girls. But boys feel it too. And it’s not just purely visual content. The trigger can simply be love of a certain musical genre.

‘Zyzz hardstyle’ remixes can also be heard in videos directly attacking women—on the same Instagram pages, one finds compilations with tens of thousands of likes depicting women as unfaithful, unworthy of attention, placing exaggerated and superficial demands on the appearance of men, or just as sexual objects distracting from exercise. A common comment under posts like these is the simple remark: "Women.. ☕."

The leap from listening to electronic music to hating your body or women can seem far-fetched. But the media is full of similar stories, raising the question: Are these radical positions really all that niche? “You're watching something about teen fashion and then the next thing you know, the algorithm would push you to a Ben Shapiro video.” That’s how user Reid Brown described, to CBC, his journey from innocent content to influential American conservative commentator Shapiro—who claimed, among other things, that homosexual and transgender identities are psychological disorders.

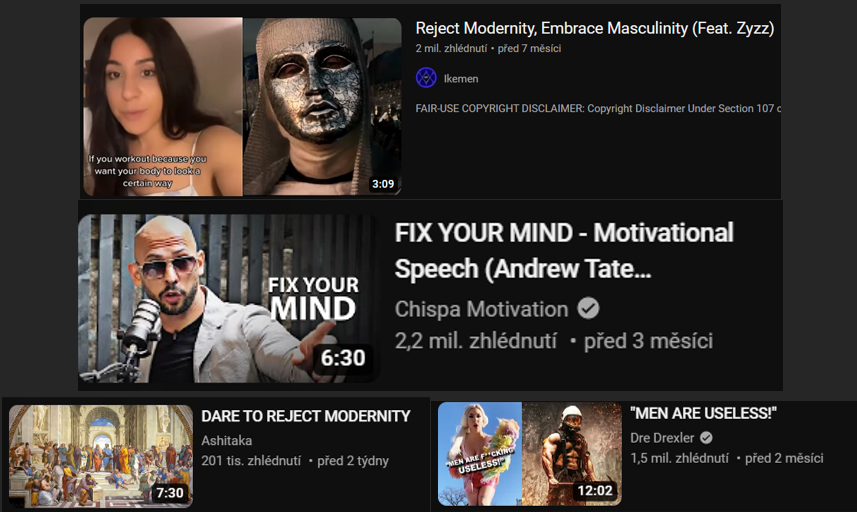

I had to try this out myself. In an anonymous browser, I watched the most viewed Zyzz hardstyle on YouTube. Among the first recommended non-musical videos were nearly identical compilations entitled Reject modernity, embrace masculinity (or a variation on this title). Alongside Zyzz, these videos quote footage from anime and ‘manly’ films like Fight Club, American Psycho, and 300: Battle of Thermopylae, and a number of figures from the American far-right, including podcaster Joe Rogan and psychologist Jordan Peterson. To contrast this show of ‘masculinity’, these videos also show the ‘modernity’ one ought to reject—skinny boys, guys in dresses, and women live-streaming and dancing on camera.

After clicking on one of these compilations, YouTube recommended dozens of similar videos—among them, one called Fix your mind with two million views, composed of quotations from influencer Andrew Tate, who actively claims to be a sexist and a misogynist, believes that women belong to men as their property, and has been under investigation on suspicion of rape, human trafficking, and involvement in organized crime.

I wasn’t clicking particularly purposefully, and still, YouTube threw about 100 more videos of this type at me. Tate's quotes in the Fix your mind video, at first glance, gives similar, perhaps harmless, life advice as Zyzz—fight for your dreams, ‘man up’, and don’t be put off by your lack of height, because that’s what losers do. A seemingly distant corner of the internet speaks to millions of young men online, highlighting a slippery demarcation between the niche and the mainstream. Unsurprisingly and sadly, patriarchal masculinity and misogyny seem to resonate and climb to the surface—no matter how much you try to hide them.

YouTube recommended videos after watching a Zyzz hardstyle video. [Collage].

Digital environments and online music communities tend to be portrayed in the media (and often rightly so) as spaces of free expression, experimentation, the search for kindred communities, and places for identities that would face ridicule and non-acceptance in the outside world. But freedom of expression also aids the popularity of communities hating on skinny guys, women, and espousing other problematic ideologies. Music, then, serves as a strong interpersonal bond as it has for thousands of years, with this effect now amplified by the connecting and anonymizing power of the internet.

Step to the Algo-rhythmNaturally, music scenes and subcultures change, accept new influences, evolve. But it is a shame when an influential community (Zyzz worshipers) enters a music genre (hardstyle) due to the influence of social networks (e.g., TikTok), changing not only how the music sounds, but also what opinions and visuals become associated with it. A look at the hardstyle section on the Reddit forum reveals posts and discussions of fans asking why the genre became connected to bodybuilding, and why one specific form of it has started to dominate social media— the afore-mentioned ‘Zyzz hardstyle’ based on remixes of popular hits. “Beware: don’t open Zyzz playlists. I did click on some of the links … Right now, my Spotify algorithm has been all f*d up. I’m getting the most awful Daily Mixes, Release Radars and playlists,” the user Sneeuwpoppie complains.

Online platforms shape both their users and music genres with their content. This dictating power of the platforms has taken its toll not only on hardstyle, but its effects also extend to the phonk and hyperpop music scenes, which the streaming platform Spotify has stripped of most of their depth and complexity with its editorial playlists. Seeking to maximize clicks and listens, Spotify created playlists often containing only the most popular songs and subgenres of these scenes, thereby reducing and emptying their diversity: “It has the potential to kill the genre […] by flattening the vibrant phonk panorama into simply ‘trendy cowbell music’,” the YouTuber yokai explains in an interview with Kieran Press-Reynolds for the NoBells blog.

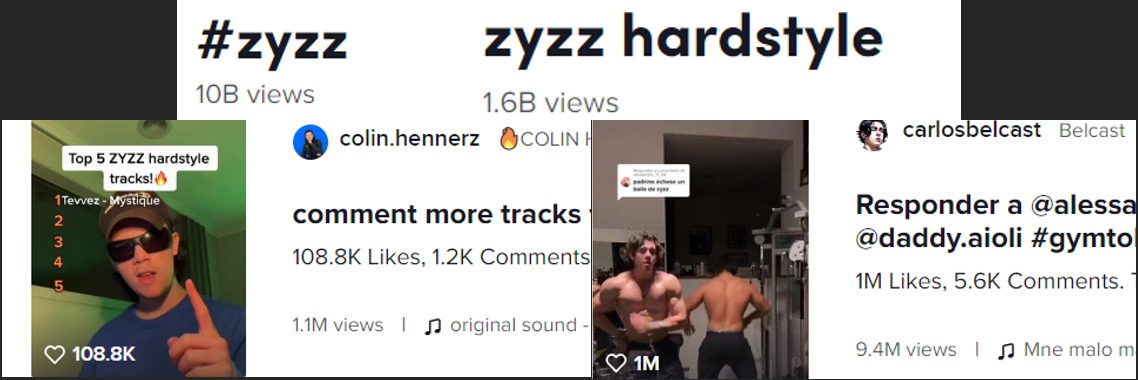

Hardstyle also faces this risk due to the obvious interest in Zyzz remixes. Videos with a combination of the hashtags #zyzz and #hardstyle have garnered over 10 billion views on TikTok alone, and many creators presumably use these hashtags as a tool to increase their reach. It is therefore very easy for fans of hardstyle or working out to come across content related to Zyzz. Algorithms simply recommend what other people clicked on next, which can be an issue if the algorithms are trained on radicalized users. A single video with the word ‘Zyzz’ in the title or caption will prompt the platform to recommend other related content, this time perhaps more controversial than the last.

This radicalizing effect of algorithms (the so-called echo chamber) is described in a study by an international team of researchers: “A viewer begins to engage with this type of content and likely falls into an algorithmic rabbit hole, with recommendations becoming increasingly dominated by such harmful content and beliefs, which also becomes increasingly extreme.” They illustrate this phenomenon with the extensive online community of incels, i.e. men in a so-called ‘involuntary celibacy’, blaming women for their own failures in intimate life. This is due to women, according to the incels, exclusively choosing genetically more suitable individuals—with taller height, bigger muscles, or a more well-defined jaw. Zack Beauchamp describes incels for Vox magazine: “It’s a new kind of danger, a testament to the power of online communities to radicalize frustrated young men based on their most personal and painful grievances.”

This mentality is highly reminiscent of the admins and followers of the aforementioned Zyzz Instagram pages, who seek acceptance and community in a shared obsession with traditional masculinity and disdain for women. The similarity with other related communities is obvious. The Underwire blog sarcastically writes, “A regime of deadlifts, anti-feminism, and red pills will turn any incel/wimp/beta/cuck into a ripped alpha male who resists the temptations of the women who desire him after years of rejection.”

Motivation to get out of BedZyzz as a role model works both ways. He inspires harmful attitudes, but on the other hand, there are testimonies in the online bodybuilding and hardstyle community of how he gave young men (and sometimes women) self-confidence, motivated them to go to the gym, listen to hardstyle, or stop taking drugs.

The fact that the potentially positive effects of male icons like Zyzz are often accompanied by problematic ideologies, only points to the current crisis of masculinity. In his study Constructing narratives of masculinity, researcher Nesbitt-Larking writes about young men who often look for role models in an attempt to find out what masculinity actually means and who they should be in a society that’s being transformed by feminism. They find their answers not in feminist texts, but in Zyzz, Shapiro, or Peterson, who, according to Nesbitt-Larking, serve as the focus of “the attention of millions of young men in a virtual global village looking for clues of masculine identification and validation.”

Instead of showing the way forward, these influential figures point backwards—to the comfort of traditional gender roles, defined masculine identity, and catering to young white men who feel anxious and threatened by losing their long-held power over women.

When your identity is going through a crisis, it makes sense to gather around a virtual bonfire to the beat of hardstyle, with a common interest in working out, making memes, and getting inspiration from shared role models. However, the culture-shaping potential of digital spaces dedicated to music and memes must be viewed in a new light. Undoubtedly creative, inspiring, and limit-pushing music scenes are giving way to avant-garde or suppressed needs—the aforementioned phonk and hyperpop scenes in their "original" forms are a nice example of this. However, the architecture of both music platforms and social networks, their echo chambers, anonymity, and viral potential of memes, also threatens to push limits that should remain where they are. And sometimes the boundary between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ is hard to see.

There is nothing wrong with working out, listening to hardstyle remixes of radio hits, and even watching motivational YouTube clips. However, there are mechanisms that do not distinguish between right and wrong, and they are built into the bowels of the platforms through which we interact with music, videos, and text. Even seemingly innocent content such as bizarre remixes of pop hits can be linked to hateful ideologies through algorithms. Because what tech companies and their algorithmic fingers care about the most is activity, clicks, and interactions—and on the internet, moral categories often just get in the way.

‘Gym internet music’ is making waves, apparently, and shows how various online subcultures can reveal a treasure trove of things that’ll rip your ears off and leave you longing for more. Clicking through these sonic rabbit holes, however, can also quickly lead to dark places you may wish you hadn’t discovered.

Meme music seems to be the next big thing. Robloxcore, Dariacore, Signalwave, Sigilkore… British and American media have described such eclectic experimental scenes deep fried in internet culture as the future of pop for gen Z. But despite their attractively unhinged Bit- and soul-crushing nature, a quick scroll through SoundCloud still reveals this type of music to be a very niche thing. Look beyond a few select trends, and you’ll quickly find songs with a similar aesthetic buried in the internet depths, doomed to oblivion. The chronically online revolution isn’t happening for everyone. Hectic furcore “tinnitus speedrun” attempts, borderline illegal lolicore mixes, breakcore versions of traditional Czech folk music. It’s all here for the passionate insiders to enjoy, but in the outside world, no one is really paying attention. You probably won’t catch your classmates gushing over “funnycore twerkhouse” anytime soon.

It is all the more surprising, then, to discover one particular trend booming in such a big way. The combination of hardstyle—a hard hitting electronic dance genre originating from turn-of-the-century Netherlands rave scenes—and gym culture—which adapted the music’s frantic beats and high-octane energy to serve as the perfect workout music—created the fertile soil for the birth of a new social media trend.

By uploading hardstyle- and gym-themed remixes, often of 00’s and 10’s radio hits, users get substantial algorithmic traction across platforms. Their YouTube and SoundCloud profiles work as ideal ‘viral factories’, posting content reminiscent of the nightcore trend of the early 2000s—simple, formulaic remixes with generic beats inserted into sped-up popular songs. Due to their simplicity, these tracks can be dished out one after the other, pleasing the platforms' algorithms. The more user activity, the more social networks earn.

Tracks related to gym and hardstyle amass millions of plays across platforms

Pumping out the Hardstyle BangersBut why are these tracks so popular? As with much of today's teenage internet culture, TikTok plays a big role here. Videos with the hashtags #gymmusic or #gymhardstyle garner tens of millions of views, featuring jacked up guys recommending the best bass-boosted mixes with chipmunk vocals, or showing heavily edited fancams of bodybuilders intended to juice up your next bench press session. These songs and videos function as memes—they contain strong visual and edited language, humor, remix, are easily and virally replicable, encourage further dissemination and, most importantly, help unite a specific community around a shared topic.

Another related hashtag almost always appears with the songs: #zyzz. The connection between hardstyle and working out is partly owed to Aziz Shavershian (known as Zyzz)—an idol of the online bodybuilding community, fitness influencer, and a die-hard fan and promoter of hardstyle. Famous for his perfect figure, internet trolling, and steroid use, this Australian bodybuilder gained cult status in the last decade following his untimely death in 2011 at the age of just 22.

Zyzz's love of working out and hardstyle is the inspiration behind a specific genre of very popular gym remixes called ‘Zyzz hardstyle’ or ‘ZYZZCORE’. Compilations titled “When the Zyzz Music Kicks In” are used by millions of users as the ultimate workout motivation. These compilations feature banging tracks by the artist Tevvez, a staple in the Zyzz-lovers community, accompanying videos of men pushing the physical limits on how big a person’s biceps can possibly get. Shavershian was even recently celebrated by Australian producer Flume, who performed alongside Zyzz's brother and a group of oiled-up bodybuilders, showing how this trend is reaching mainstream music as well.

The popularity of motivational workout content on YouTube is skyrocketing.

Disregard Females. Acquire AestheticsOf course, this could just be harmless fun. The character of Zyzz, however, who is almost always mentioned in the captions, titles, and hashtags of these ‘fun’ remixes—be it of Katy Perry, Maroon 5, or Lana Del Rey—raises many red flags. Zyzz became famous for numerous posts circulating on the Bodybuilding Forum and 4chan’s fitness section, in which he preached recipes for the ‘perfect’ lifestyle: exercise 5 times a day, drink vodka, be an alpha male, “disregard females, acquire aesthetics.”

To this day, Zyzz is an icon of fitness TikTok ( ‘GymTok’) and a number of TikTok and Instagram profiles which post memes, inspirational photos, and videos adoringly showing off his muscles and masculinity, while at the same time body-shaming those whose bodies look different. “One of GymTok’s biggest problems is its obsession with ‘masculinity’ and eliminating ‘weakness’” writes Lucca Swain for The Owl.

The Instagram profile @zyzz_page is overflowing with photos of absurdly muscular men, whilst its frequent collaborator profile @gym_or_meme, makes fun of guys who are overweight or wear makeup. Zyzz and others like him thus serve as an inspiration and pipeline for body-shaming content, sometimes causing muscle dysmorphia (also called ‘bigorexia’)—a kind of reverse anorexia, a chronic idea of ‘being too small’ and an obsession with gaining muscle and working out. “The never-ending scroll of six packs and boy-band faces makes [young men] feel inadequate and anxious,” writes Alex Hawgood for the New York Times, describing the influence of social media on the development of the illness.

The IG profile @zyzz_page compares the sons of Arnold Schwarzenegger. [Collage].

The problems of beauty standards promoted by online environments were, until recently, addressed in the media and academia mainly for girls. But boys feel it too. And it’s not just purely visual content. The trigger can simply be love of a certain musical genre.

‘Zyzz hardstyle’ remixes can also be heard in videos directly attacking women—on the same Instagram pages, one finds compilations with tens of thousands of likes depicting women as unfaithful, unworthy of attention, placing exaggerated and superficial demands on the appearance of men, or just as sexual objects distracting from exercise. A common comment under posts like these is the simple remark: "Women.. ☕."

A video of famous TikToker Bella Poarch dancing, interspersed with shots of men hitting the gym. A Zyzz hardstyle remix plays in the background.

Expressing Suppressed IdentitiesIt sounds like under a layer of anime profile pictures and sped-up chipmunk remixes of Katy Perry, there’s an online scene of young gym bros worshiping the posthumous legacy of a controversial icon connected with a harmfully masculine and misogynistic subculture. Let’s hope the situation is not as dire as it seems, and that a large part of hardstyle listeners disagree with these hateful attitudes and are simply teenagers who like working out, fast music, and cartoons. But these teens might be just a few clicks away from changing their minds. Almost half a million followers of the above-mentioned IG profiles have a different worldview—and they show what social networks and internet music can serve as a staging ground for.The leap from listening to electronic music to hating your body or women can seem far-fetched. But the media is full of similar stories, raising the question: Are these radical positions really all that niche? “You're watching something about teen fashion and then the next thing you know, the algorithm would push you to a Ben Shapiro video.” That’s how user Reid Brown described, to CBC, his journey from innocent content to influential American conservative commentator Shapiro—who claimed, among other things, that homosexual and transgender identities are psychological disorders.

I had to try this out myself. In an anonymous browser, I watched the most viewed Zyzz hardstyle on YouTube. Among the first recommended non-musical videos were nearly identical compilations entitled Reject modernity, embrace masculinity (or a variation on this title). Alongside Zyzz, these videos quote footage from anime and ‘manly’ films like Fight Club, American Psycho, and 300: Battle of Thermopylae, and a number of figures from the American far-right, including podcaster Joe Rogan and psychologist Jordan Peterson. To contrast this show of ‘masculinity’, these videos also show the ‘modernity’ one ought to reject—skinny boys, guys in dresses, and women live-streaming and dancing on camera.

After clicking on one of these compilations, YouTube recommended dozens of similar videos—among them, one called Fix your mind with two million views, composed of quotations from influencer Andrew Tate, who actively claims to be a sexist and a misogynist, believes that women belong to men as their property, and has been under investigation on suspicion of rape, human trafficking, and involvement in organized crime.

I wasn’t clicking particularly purposefully, and still, YouTube threw about 100 more videos of this type at me. Tate's quotes in the Fix your mind video, at first glance, gives similar, perhaps harmless, life advice as Zyzz—fight for your dreams, ‘man up’, and don’t be put off by your lack of height, because that’s what losers do. A seemingly distant corner of the internet speaks to millions of young men online, highlighting a slippery demarcation between the niche and the mainstream. Unsurprisingly and sadly, patriarchal masculinity and misogyny seem to resonate and climb to the surface—no matter how much you try to hide them.

YouTube recommended videos after watching a Zyzz hardstyle video. [Collage].

Digital environments and online music communities tend to be portrayed in the media (and often rightly so) as spaces of free expression, experimentation, the search for kindred communities, and places for identities that would face ridicule and non-acceptance in the outside world. But freedom of expression also aids the popularity of communities hating on skinny guys, women, and espousing other problematic ideologies. Music, then, serves as a strong interpersonal bond as it has for thousands of years, with this effect now amplified by the connecting and anonymizing power of the internet.

Step to the Algo-rhythmNaturally, music scenes and subcultures change, accept new influences, evolve. But it is a shame when an influential community (Zyzz worshipers) enters a music genre (hardstyle) due to the influence of social networks (e.g., TikTok), changing not only how the music sounds, but also what opinions and visuals become associated with it. A look at the hardstyle section on the Reddit forum reveals posts and discussions of fans asking why the genre became connected to bodybuilding, and why one specific form of it has started to dominate social media— the afore-mentioned ‘Zyzz hardstyle’ based on remixes of popular hits. “Beware: don’t open Zyzz playlists. I did click on some of the links … Right now, my Spotify algorithm has been all f*d up. I’m getting the most awful Daily Mixes, Release Radars and playlists,” the user Sneeuwpoppie complains.

Online platforms shape both their users and music genres with their content. This dictating power of the platforms has taken its toll not only on hardstyle, but its effects also extend to the phonk and hyperpop music scenes, which the streaming platform Spotify has stripped of most of their depth and complexity with its editorial playlists. Seeking to maximize clicks and listens, Spotify created playlists often containing only the most popular songs and subgenres of these scenes, thereby reducing and emptying their diversity: “It has the potential to kill the genre […] by flattening the vibrant phonk panorama into simply ‘trendy cowbell music’,” the YouTuber yokai explains in an interview with Kieran Press-Reynolds for the NoBells blog.

Hardstyle also faces this risk due to the obvious interest in Zyzz remixes. Videos with a combination of the hashtags #zyzz and #hardstyle have garnered over 10 billion views on TikTok alone, and many creators presumably use these hashtags as a tool to increase their reach. It is therefore very easy for fans of hardstyle or working out to come across content related to Zyzz. Algorithms simply recommend what other people clicked on next, which can be an issue if the algorithms are trained on radicalized users. A single video with the word ‘Zyzz’ in the title or caption will prompt the platform to recommend other related content, this time perhaps more controversial than the last.

Hashtags #zyzz and #zyzz hardstyle with billions of views. [Collage].

This radicalizing effect of algorithms (the so-called echo chamber) is described in a study by an international team of researchers: “A viewer begins to engage with this type of content and likely falls into an algorithmic rabbit hole, with recommendations becoming increasingly dominated by such harmful content and beliefs, which also becomes increasingly extreme.” They illustrate this phenomenon with the extensive online community of incels, i.e. men in a so-called ‘involuntary celibacy’, blaming women for their own failures in intimate life. This is due to women, according to the incels, exclusively choosing genetically more suitable individuals—with taller height, bigger muscles, or a more well-defined jaw. Zack Beauchamp describes incels for Vox magazine: “It’s a new kind of danger, a testament to the power of online communities to radicalize frustrated young men based on their most personal and painful grievances.”

This mentality is highly reminiscent of the admins and followers of the aforementioned Zyzz Instagram pages, who seek acceptance and community in a shared obsession with traditional masculinity and disdain for women. The similarity with other related communities is obvious. The Underwire blog sarcastically writes, “A regime of deadlifts, anti-feminism, and red pills will turn any incel/wimp/beta/cuck into a ripped alpha male who resists the temptations of the women who desire him after years of rejection.”

Fans of @zyzz_page find their role models in the Doomer character or psychopath Patrick Bateman. [Collage].

Motivation to get out of BedZyzz as a role model works both ways. He inspires harmful attitudes, but on the other hand, there are testimonies in the online bodybuilding and hardstyle community of how he gave young men (and sometimes women) self-confidence, motivated them to go to the gym, listen to hardstyle, or stop taking drugs.

The fact that the potentially positive effects of male icons like Zyzz are often accompanied by problematic ideologies, only points to the current crisis of masculinity. In his study Constructing narratives of masculinity, researcher Nesbitt-Larking writes about young men who often look for role models in an attempt to find out what masculinity actually means and who they should be in a society that’s being transformed by feminism. They find their answers not in feminist texts, but in Zyzz, Shapiro, or Peterson, who, according to Nesbitt-Larking, serve as the focus of “the attention of millions of young men in a virtual global village looking for clues of masculine identification and validation.”

Instead of showing the way forward, these influential figures point backwards—to the comfort of traditional gender roles, defined masculine identity, and catering to young white men who feel anxious and threatened by losing their long-held power over women.

Zyzz’s motivational quote, which has become somewhat of a meme.

When your identity is going through a crisis, it makes sense to gather around a virtual bonfire to the beat of hardstyle, with a common interest in working out, making memes, and getting inspiration from shared role models. However, the culture-shaping potential of digital spaces dedicated to music and memes must be viewed in a new light. Undoubtedly creative, inspiring, and limit-pushing music scenes are giving way to avant-garde or suppressed needs—the aforementioned phonk and hyperpop scenes in their "original" forms are a nice example of this. However, the architecture of both music platforms and social networks, their echo chambers, anonymity, and viral potential of memes, also threatens to push limits that should remain where they are. And sometimes the boundary between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ is hard to see.

There is nothing wrong with working out, listening to hardstyle remixes of radio hits, and even watching motivational YouTube clips. However, there are mechanisms that do not distinguish between right and wrong, and they are built into the bowels of the platforms through which we interact with music, videos, and text. Even seemingly innocent content such as bizarre remixes of pop hits can be linked to hateful ideologies through algorithms. Because what tech companies and their algorithmic fingers care about the most is activity, clicks, and interactions—and on the internet, moral categories often just get in the way.